Why Islands?

And what do I mean by islands anyway?

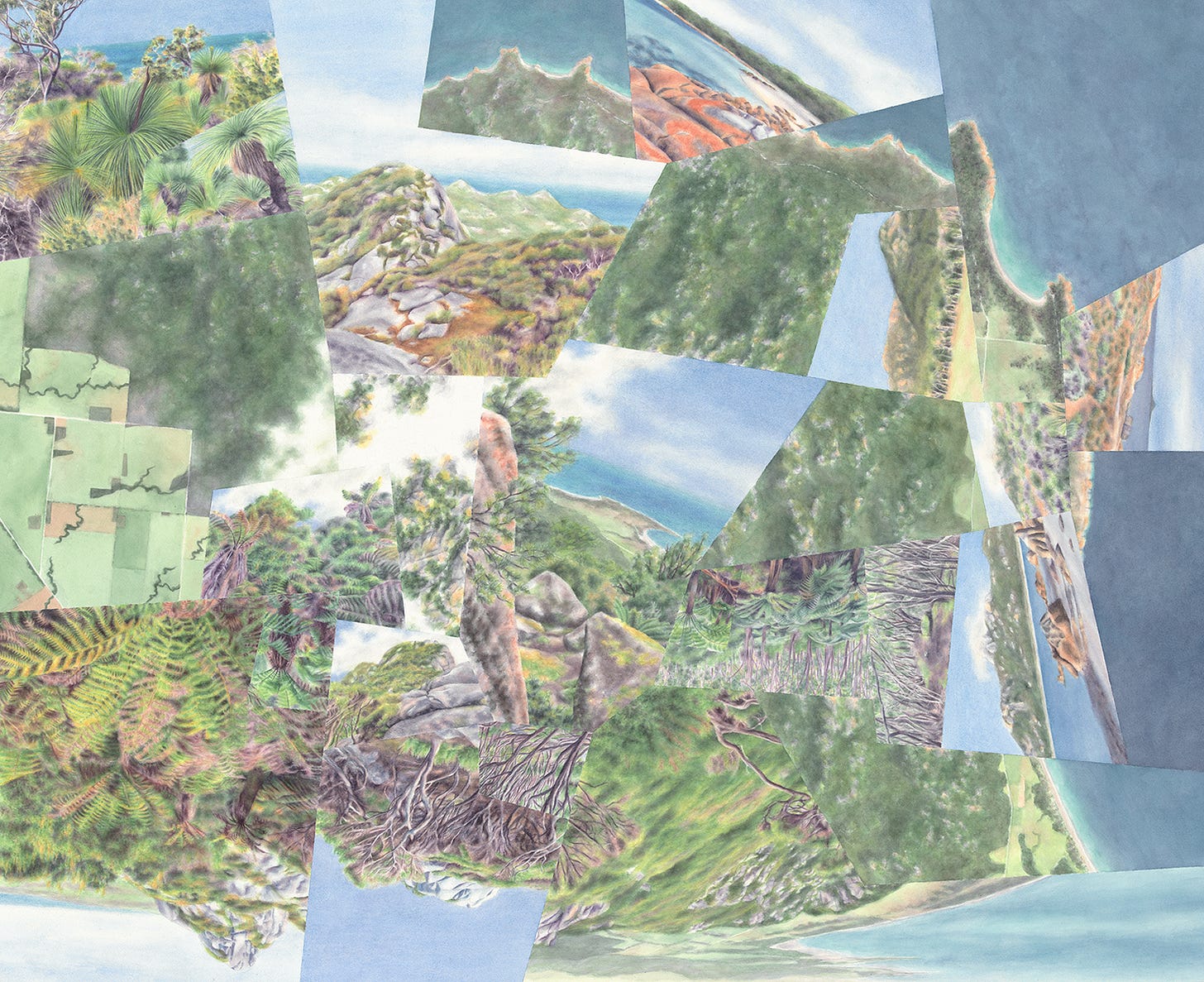

In my first two posts I introduced my process of compressing experiences—spatial and immersive at the same time—of ecological islands and edges in my watercolor maps. But why am I so drawn to these geographies in the first place? And what do I really mean by “ecological islands and edges”?

Probably most of us find islands alluring, at least the kind surrounded by water (and not necessarily related to their ecology). It pretty obviously has to do with their apart-ness—some mix of distance, uniqueness, and bounded-ness. They represent an escape from the familiar. Their main attraction for me is an inflection of this self-contained quality, but not in the sense of being separate from the wider world so much as being disconnected pieces of it that also feel like whole worlds—microcosms—unto themselves.

Islands that are distinct in terms of their natural environments strike me as compressed, miniaturized, or more clearly-delineated versions of natural conditions that are too big or undefined for us to grasp easily. The edges of these islands seem to be unexpected or unexpectedly abrupt, slicing nature up into more manageable and “knowable” pieces. Experiencing these edges—ideally traveling from one edge to another across an island and then tracing the whole perimeter—gives me what I think of as an empowering world-at-my-fingertips feeling. It’s basically a sensation of control or omniscience, certainly related to the general human urge to figuratively slice up and order the natural world though mapping it or classifying it.

My goal in the watercolor maps is to heighten this world-at-my-fingertips feeling I get from real islands and their edges by compressing and sharpening them even further. The cartographic mosaics are more dramatically sliced-up versions of the actual, geographical mosaics1—you could say it’s an idiosyncratic take on what all maps try to accomplish on some level.

Before going further, I need to acknowledge that this desire to graphically structure and slice up nature, in my own maps and in maps in general, has its problematic side—both reflecting and reinforcing the obvious problems with physically controlling and carving up the natural world. I’ll get into that a lot more later, because it’s actually become, inadvertently, part of the theme of the maps too.

As you’ve noticed I use island in a very broad sense, to an extent that might be a bit confusing. I specify ecological to make it obvious that I’m referring to a lot more than just water-defined islands, but I’m a little inconsistent with that modifier because I don’t want to suggest that those islands don’t apply too. (Though even in that case, it’s still the ecology and vegetation that I tend to focus on.) In fact the kinds of islands captured in the watercolor maps can be broken down into four general categories, and you’ll see that both terms can be misleading for other reasons as well. But I think that used together they’re still best at covering the full range.2

Here are those four categories, organized around how the islands are formed or defined.

From above. In this type the environmental conditions creating the island come mainly “from above” in the form of temperature and precipitation. Of course they’re never independent from facts on the ground, and it’s usually mountain topography that compresses continent-scale climatic/ecological patterns—biomes or ecoregions—down to more easily perceptible ecozones. These islands might be forests on mountains in deserts, or alpine zones on mountaintops in forests. Or both. Often (if not usually) this is actually about island clusters, ranging from roughly concentric to sequenced or grouped in “archipelagos.” The complexity of these clusters is the main reason I keep throwing in edges3 too: islands in this category seem a little less island-like when they’re not alone, meaning the pattern of edges is just as prominent.

From below. This type of island is created most directly by conditions on or below the surface. So this covers “actual” islands (in water), as well as groundwater-fed desert oases. But besides hydrology, rock or soil type (substrate) can also create an island of a particular ecosystem or vegetation type.

Land use. Here, land uses like urbanization or agriculture surround isolated remnants of native ecology. (Ecological island is arguably a stretch here given that the island only exists because of non-ecological factors, except under a very broad definition of ecological.)

From even farther below (volcanism). This category stands apart from the other three because it’s purely about geology and landform, rather than vegetation. It’s about volcanic cones and craters, clearly standing out from the surrounding landscape, that are small enough and (temporarily at least) quiet enough to easily access and explore. I find these more inspirational than just regular mountains: similar to larger-than-life-climatic patterns in the 1st category, here something big, powerful, and often dangerous is being squeezed down to a more human scale and understanding.

These four island types often overlap—like a volcano in the middle of a city, or an oceanic island with a lot of topography and ecological complexity. (The Big Island of Hawaii isn’t the most spatially “compressed” oceanic island but it’s worth mentioning as an example since it’s often called an island-continent.)

The watercolor cartography is inspired by a mix of these categories, sometimes mixed within the same map. And while the types aren’t particularly obscure, and I’m sure the microcosm aspect is part of the allure of islands for many people, I haven’t found much said about this sensation of empowerment that draws me to them. I also haven’t come across any other artwork or cartography that tries to capture it. Maybe that’s because nobody else feels it, especially no one who thinks of doing something creative with it? I’d bet, though, that I’m not the only one. So, if this world-at-my-fingertips effect is something you’ve picked up on, or that strikes a chord now that you’re hearing it from me, I’d love to know about it.

So, there’s an overview of my higher-level inspiration, and a bit of a slog through definitions that I needed to get out of the way. Next time I’ll start diving more into specific maps and places! And remember that you can also get these thoughts and (many more) images in video form too on my YouTube channel.

-Darren

Some of my thinking on these islands is connected to the field of landscape ecology—I borrow some terms but also purposefully replace or “misuse” some others (see notes below). Mosaic is one that I’m borrowing when I use it in reference to heterogeneity in the physical landscape. Forman, R. T. T. (1995). Land mosaics: The ecology of landscapes and regions. Cambridge University Press.

Actually there is a landscape ecology term I could use in place of ecological islands that would cover the range of geographical conditions that I want it to, and that’s patches (Forman, 1995). For example, it incorporates islands-in-water while still avoiding that narrow association. But, it lacks the poetry of islands.

An edge, most accurately, is the outer zone of what I’m calling an island but is technically a patch (see note above), rather than a line between two patches (Forman 1995). But I’m using the term more generically to mean either of those.

Wow, I've never heard so many looks and variations on islands! Even though I love them. In Arizona (and I believe it's the same for New Mexico, maybe??), we have "Sky Islands" - and they bring residents relief from the desert heat. Seeing your many aspects for islands is definitely thought-provoking!