Origins, Continued...Designing Islands

Landscape Architecture On My Own Terms

I ended my last post with my oil painting phase. Besides competing with design practice, it was starting to feel like a bit of a dead end for these island explorations.

First there was the issue I mentioned before. Taking advantage of the medium to intensify the individual scenes—giving some of them a surreal, dreamlike quality compared to the original photography—distracted from the spatial theme of capturing islands and contrasts. It was those contrasts that I really wanted to intensify. But also this whole slicing-and-juxtaposing approach, in both photomontage and oils (I’ll just call it “montage”), wasn’t actually doing enough to compensate for what landscape architecture wasn’t giving me.

Choosing that field had been the right choice. I liked the challenge of manipulating sites in ways that were constructable at least in theory—working with actual scales and dimensions—even if they did end up staying on paper. It involved a level of problem-solving that creating abstract representations didn’t. Being an artist wasn’t going to be enough. The issue was that I wasn’t designing much or at all in the kind of site—ecologically intact and diverse, usually remote and obscure—that I was the most passionate about. That didn’t mean I wasn’t finding any fulfillment in landscape architecture at all, but there was a nagging void.

So I needed to try taking landscape architecture itself in my own direction, not just filling in the gaps with other pursuits. Yes, I could’ve also looked for a different office with projects more in line with my interests—they do exist—but at the same time I’d also become disenchanted with a lot of the day-to-day workings of the profession. This combination of factors led me to begin what I thought would be a one- or two-year break from practice, enough to just get all of this out of my system.

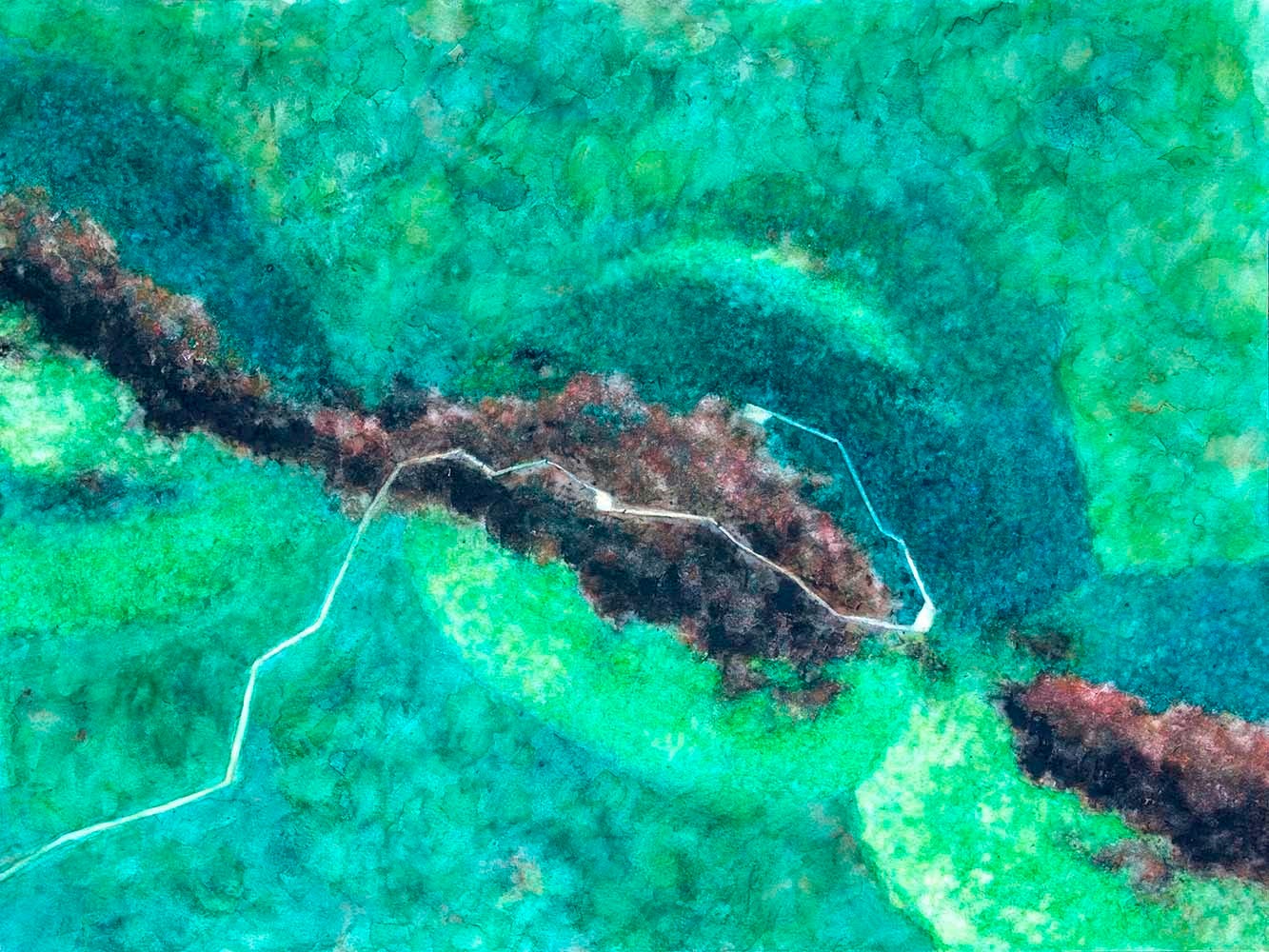

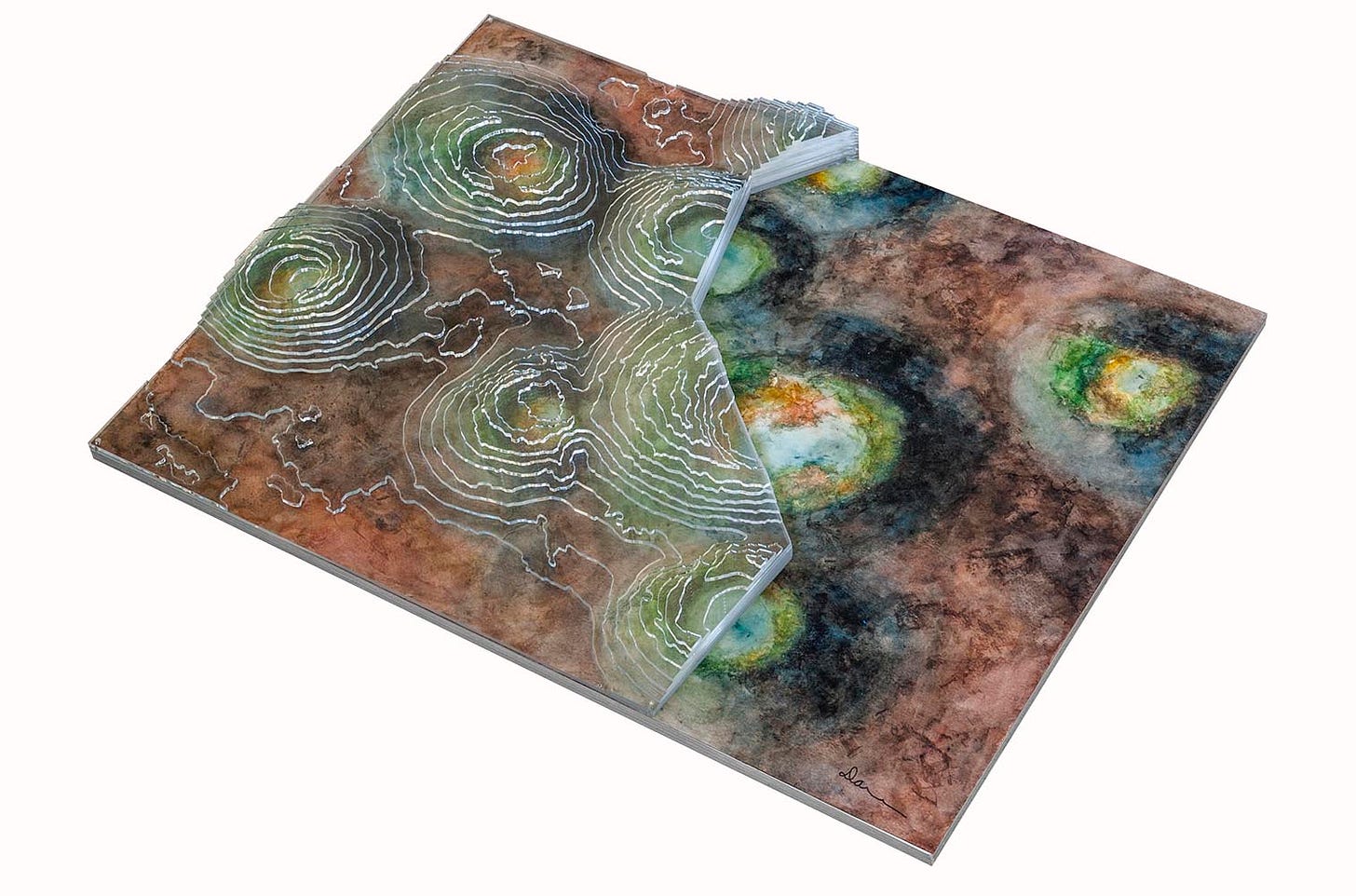

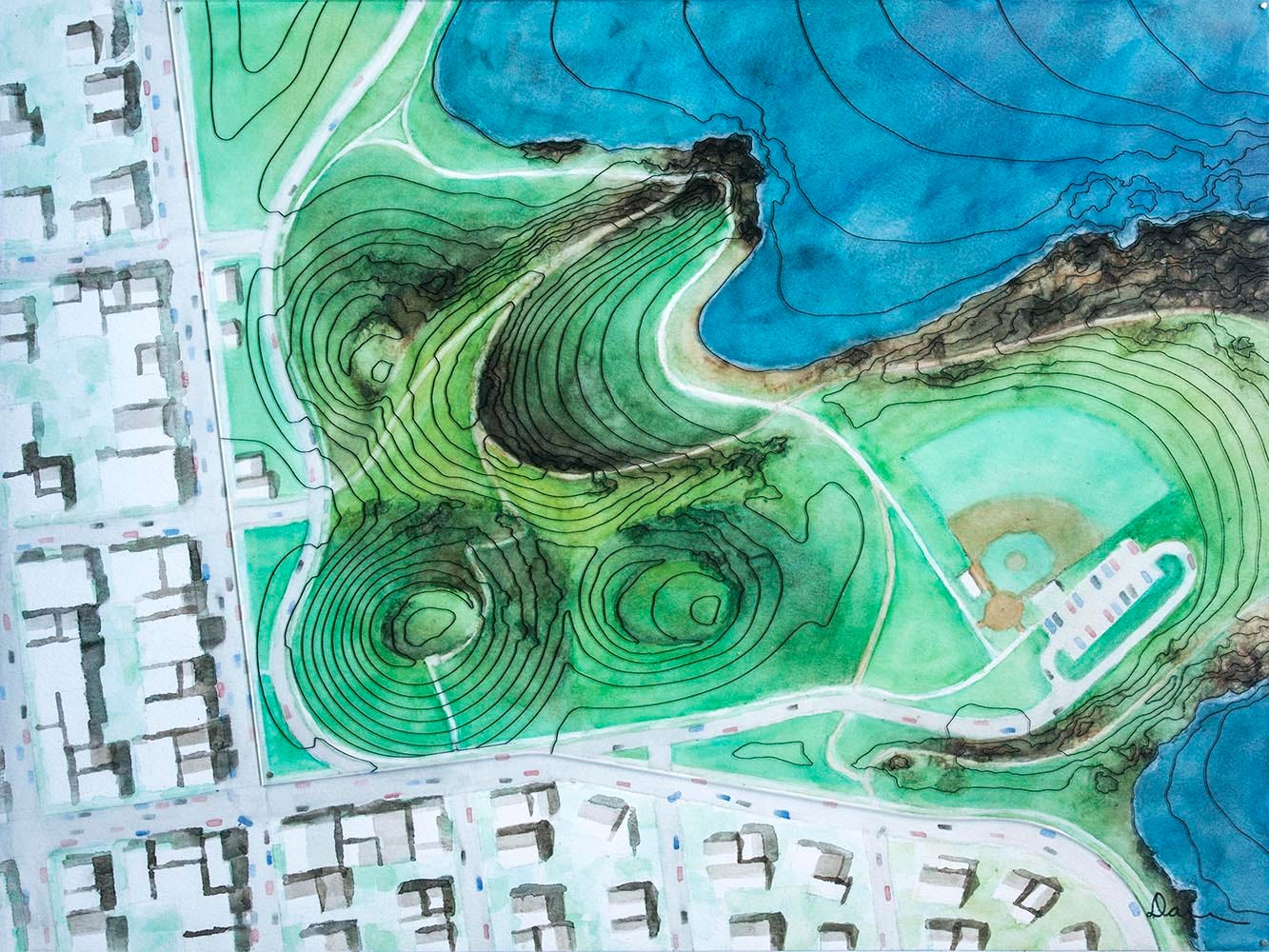

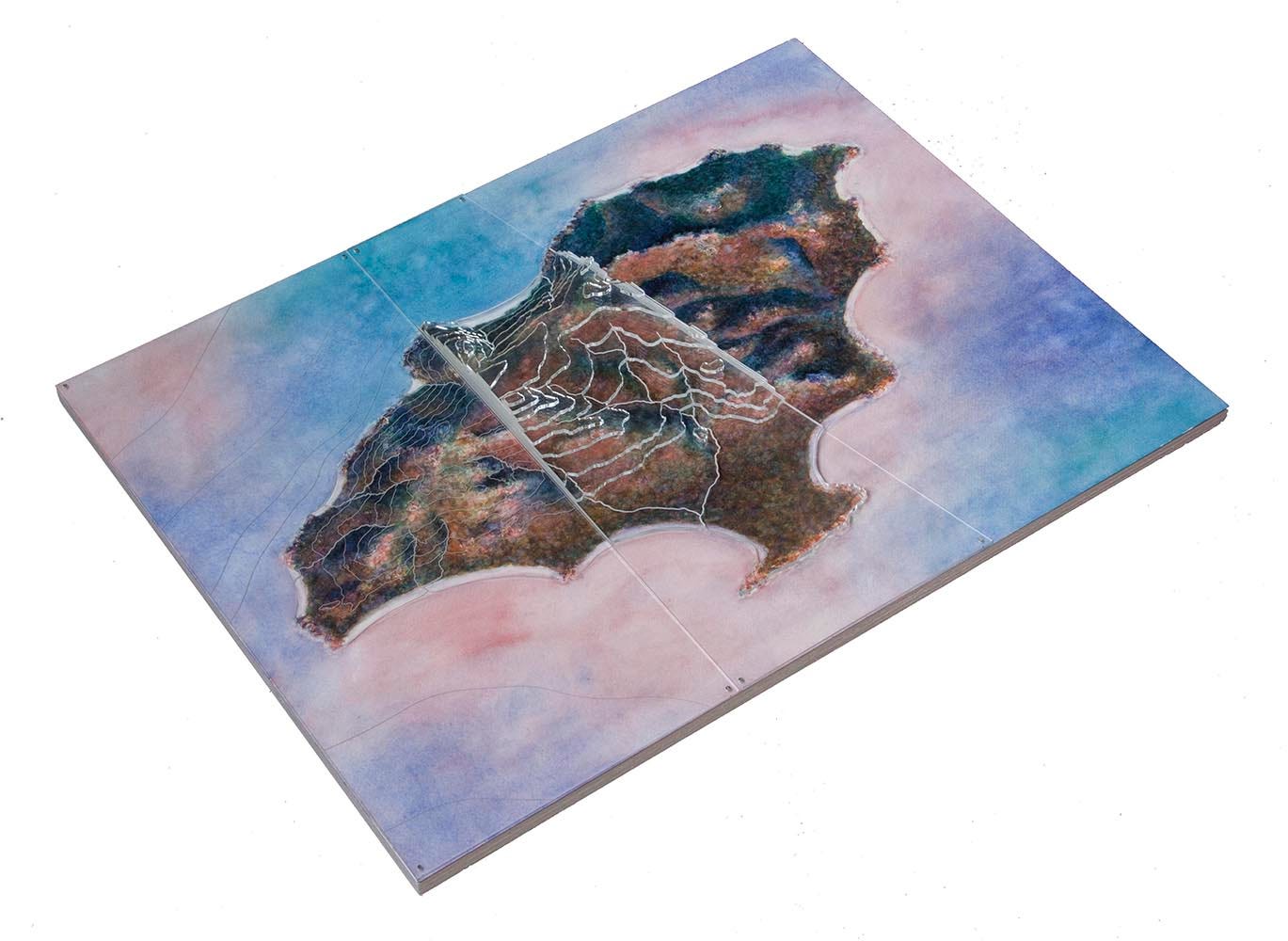

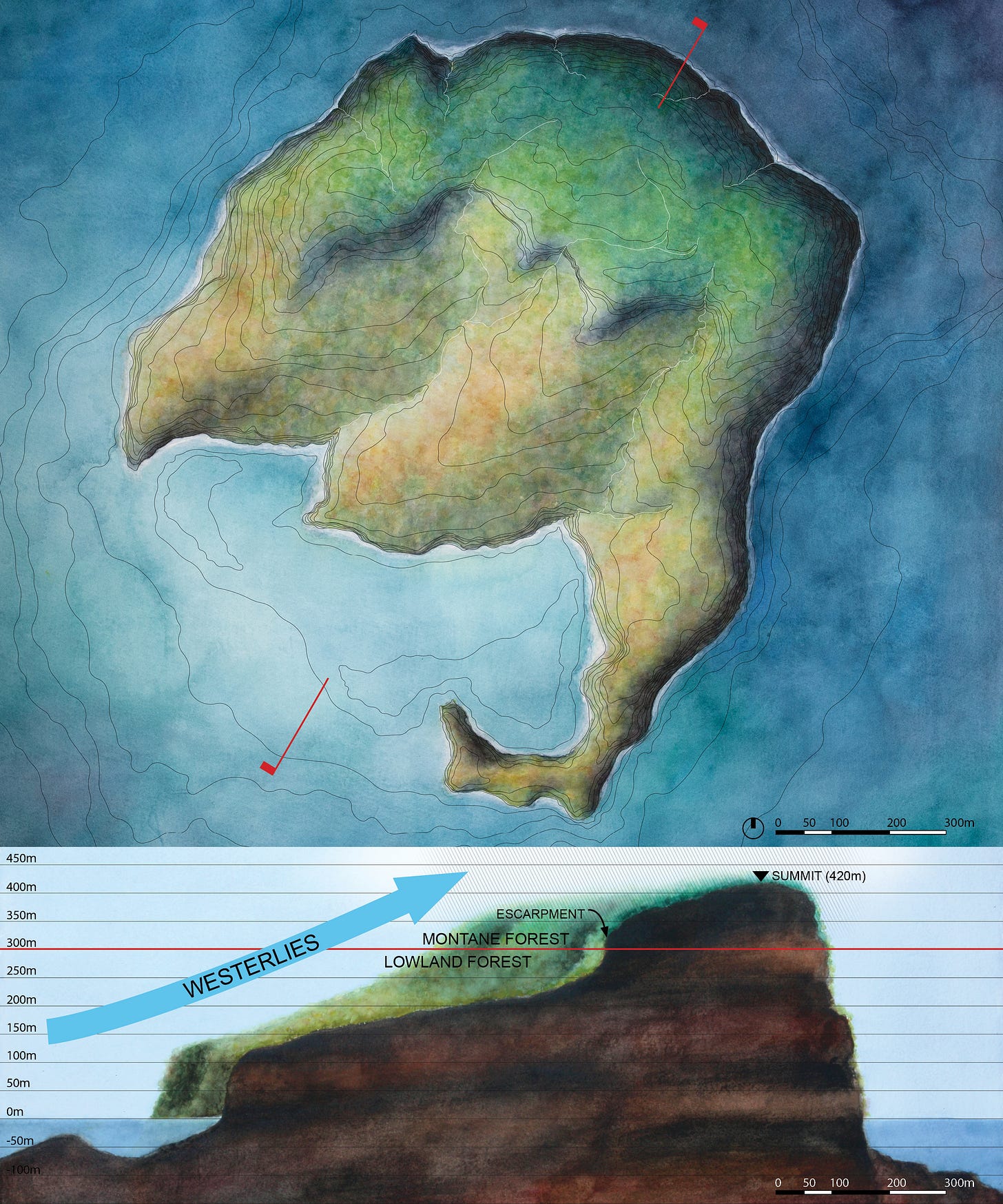

It has of course ended up extending far beyond that. But this next phase, a more straightforward extension of my design career than earlier or later ones, did last about two years. It focused on designing islands—of the four different kinds that I’ve later come to categorize—and in many cases also designing paths and structures on (or in) those islands. So I left the montaging behind and stuck to different combinations of traditional plans, section/elevations, perspectives, and physical models. The 2D views were mostly 15”x20” and in watercolor on paper, which I found better than oils for representing natural patterns and textures. I overlaid most of the plan views with representations of topography in other media (the physical models).

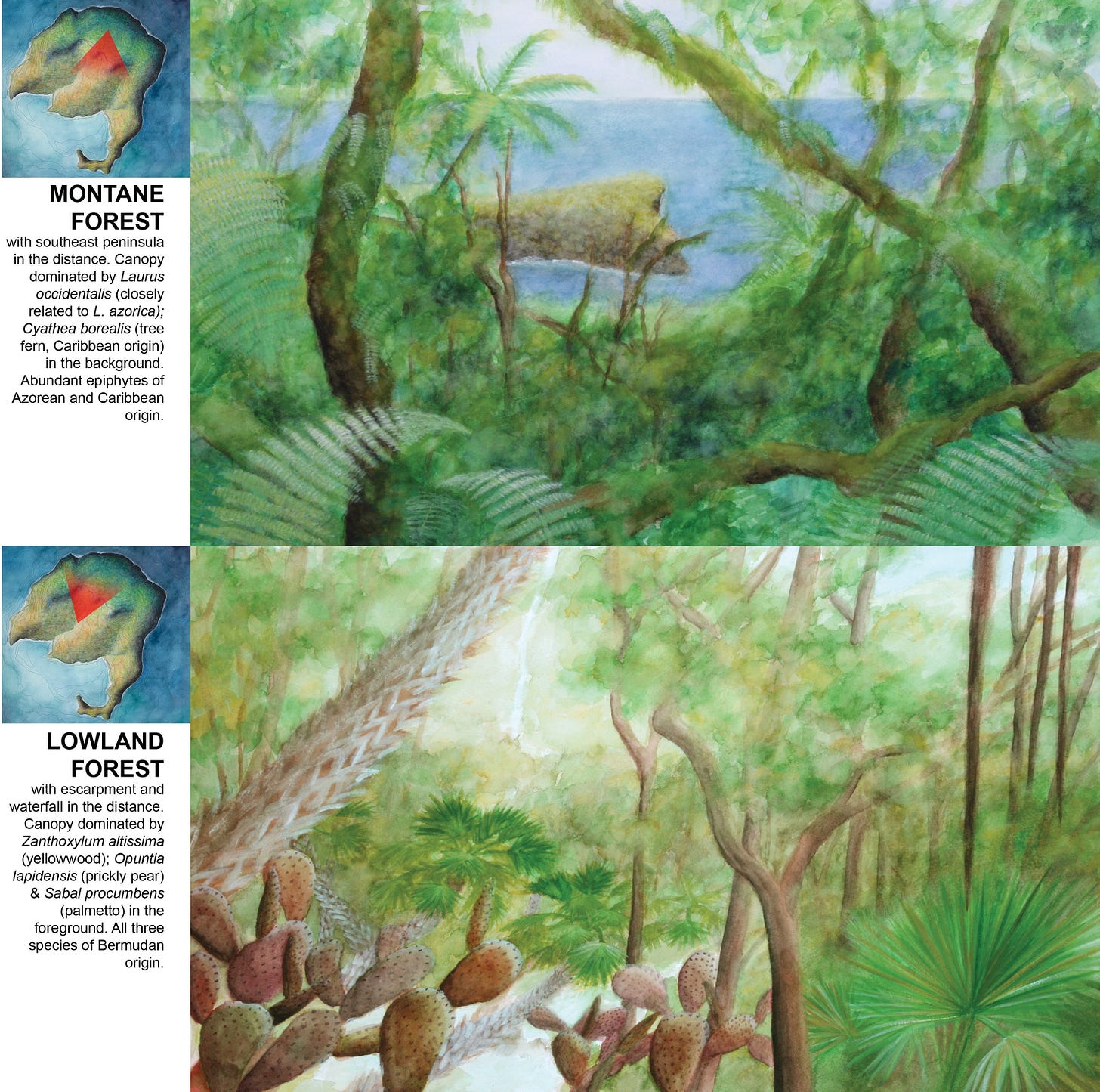

Two of these designs were Saucer Island and Shark Fin Island, each represented in a series of views at multiple scales as in a typical design project. I imagined both of these oceanic islands as compressing a crazy (i.e. impossible?) amount of ecological/climatic diversity into a tiny area, nesting together two of my island types: islands created or defined by conditions “from above” (e.g. precipitation) and “from below” (e.g. the ocean).

Saucer Island is a wide volcanic cone and crater as the name implies, so it actually checks off a third island type as well. I designed an eco-lodge near the coast of the dry western side and a series of pavilions and boardwalks on the wet, boggy rim of the eastern side, tied together by an island-wide trail system. Here’s an animation showing how the views successively zoom in on those two focal elements. (If you’re reading the email version of this and it doesn’t play, you can watch it here.) All the paintings are 15”x20,” and the overlays are marker on acetate.

I created Shark Fin Island, the name again descriptive of the form, for a design-your-own-island competition in LA+ (an interdisciplinary landscape architecture journal). This one, hypothetically located in the North Atlantic, is half-wet and half-dry too; the maximum area allowed was one square kilometer, so a dramatic slope was essential to making that contrast remotely believable. In this case there aren’t any structures to complement each of those natural conditions—I imagined the island as basically untouched. But the perspective views give a sense of this dual ecological character.

Most of the other islands are each represented only by a single work, and I stuck to plan view for the painting components. With watercolor being a new medium for me I think I still wasn’t comfortable inventing and then competently rendering views from other vantage points. If I included any 3D information at all, I captured it in the model/overlay components. Informally I call this my “Isolations” series. The majority of these designs are the product of artist residencies in Iceland and on Flinders Island off the coast of Tasmania, inspired by landscapes there with varying degrees of imagination and idealization.

First, Iceland:

Then, Australia:

And, loose inspiration from some other places:

The downsizing from the scale of the oil paintings was initially for practical reasons related to the media choice and to the goal at the beginning (with Saucer Island) of making sets of multiple paintings. Also I’d realized that the large, immersive scale of the oil paintings (in addition to the surrealist quality) was actually antithetical to the whole “compression” concept that drives me to capture and intensify these islands and contrasts in the first place. I want to convey a sense of psychologically grasping these places, of absorbing them in their entirety—not being absorbed by them.

But this idea of smallness (and related to that, rarity) in the geographical sense had started to take on another, less idiosyncratic kind of significance for me too—a quality of fragility. Most islands are, by definition, precarious in some way. The species and ecosystems within them, or the often finely-tuned environmental conditions that sustain (and isolate) those elements to begin with, are especially and increasingly vulnerable to human impacts.

Obviously, nature has been in constant flux long before the present day. That’s because of natural processes themselves along with human activity playing a significant role too over millennia. The urge to freeze in time and space the relatively intact islands that we still have, whether they exist as islands because of natural conditions or because of us, is really another form of “grasping.”

I’ll have a lot more to say about this tension between stability and change, including what it means for the whole idea of ecological fragility in the first place, later on. For now though, I’m going to take that idea at face value. Conveying this sense of fragility would be an important motivator for my work going forward, and further reason for going with the smaller scales at this stage in the evolution.

Despite the shift in dimensions (and medium) though, the plan-view watercolors would essentially end up merging with the earlier perspective-based montages, eventually kicking off the mosaic watercolor maps that I’m making now. I can trace that back to one particular work that I’ll describe in an upcoming post. It’s another one that came out of the residency on Flinders Island, inspired by that extraordinary national park which I’ll be gushing effusively about….

-Darren

Your creativity is amazing! All I can say is "Wow!"